By Scott Bremer, Emma Dyer, Linda Hirons, Jesse Schrage & Joshua Talib

ACACIA researchers are coming to see that the way we scientifically name weather systems has consequences. Names affect how societies mobilise, and how prepared they are.

This week Jesse Schrage and I (Scott Bremer) travelled from Bergen to work with ACACIA colleagues – Linda Hirons, Joshua Talib and Emma Dyer – in Reading. One of our goals was to map the network of organisations in Madagascar that govern for weather disasters, and their procedures for working together when a storm or cyclone bears down on the island. This mapping is important because the early warning systems that ACACIA develops will need to be integrated with the existing governance systems in place if they are to be useful.

The mapping work turned up many interesting insights, but one thing that gripped us was the importance of how scientists name weather systems for the knock-on choices made by the Madagascan government regarding appropriate preparations and responses. Meteorological science in Madagascar – as in most countries – is tightly interwoven with government policies, procedures, and norms for ‘disaster risk reduction’. The science and policy of storms has co-evolved, so that meteorological procedures of categorising and naming storms, and tracking their trajectories, have become mirrored in governance procedures for ‘triggering’ governance responses; evacuations, or what resources to mobilise where and when. Interestingly, these configurations of science and policy can be quite particular to national contexts; a combination of standardised global norms from the World Meteorological Organisation, for example, and nationally specific conventions.

Against this background, we saw three ways that weather naming conventions complicate governance responses.

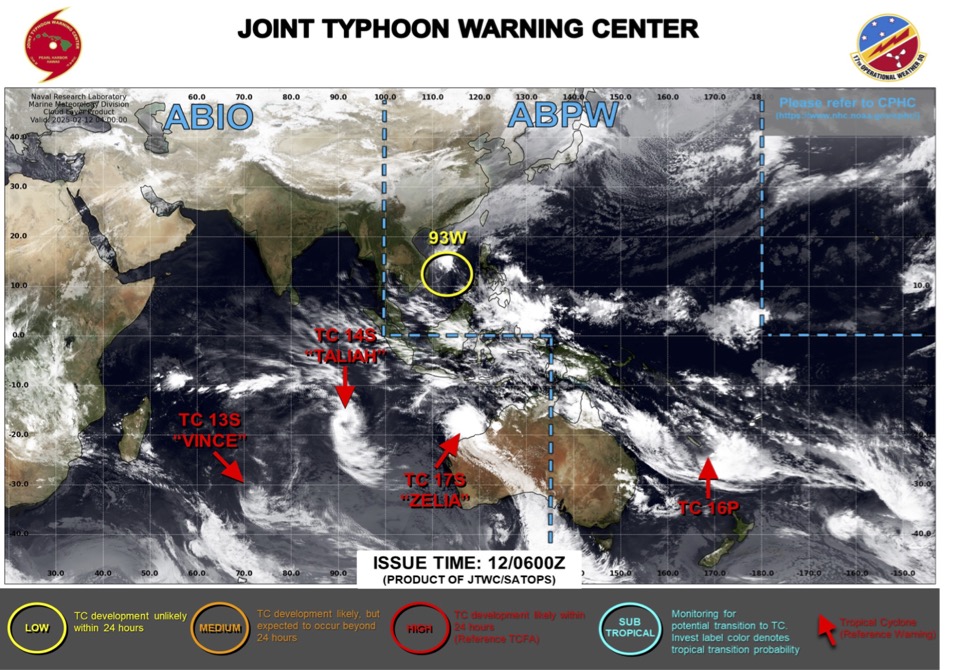

First, the conventions for classifying between cyclones, depressions, storms, and hurricanes can be confusing. As a system of rain and wind appears on a weather radar, it is classified by the strength of its winds, with one reason being to indicate how potentially destructive it can be. But how these weather systems are classified is dependent on where in the world they boil up; whether they are in the Atlantic or Pacific for example, in the tropics or in the mid-latitudes. And if this wasn’t confusing enough, these classifications overlap in inconsistent ways. I (mistakenly) assumed that the words cyclone, typhoon and hurricane were synonyms for a very strong storm, and that their use was geographic; in New Zealand they talk about cyclones, while the Americans talk about hurricanes. Moreover, in common parlance, a ‘storm’ is generally assumed to be weaker than a ‘cyclone’. So, imagine my dismay when the climate scientists in Reading pulled up a table classifying tropical cyclones as any system with winds blowing at more than 8 m/s; tropical storms as blowing faster than 17 m/s, and tropical hurricanes as exceeding 32 m/s! According to this, it seems cyclones are less severe than storms, and something different to a hurricane! We talked at length about how confusing this is for decision-makers without a meteorology background, who need to form an impression of how severe a weather system is based on common understandings of these words.

Second, it makes a big difference whether a storm is named by Madagascar’s Meteorological Department (Météo Madagascar) – given a human first name like ‘Cyclone Freddy’ in 2023 for example – or if it is left as an un-named storm. When a storm is named, this triggers a sophisticated procedure of readiness in the Madagascan government, through a largely hierarchal deployment of information and resources to areas forecast to be affected by the wild weather. This procedure is enshrined in law, with standard operating procedures; people know what to do when. But when a storm remains un-named this governmental apparatus is not activated, and communities may not receive the same early warnings or evacuation aid. This is despite many storms having significant impacts on communities – potentially equivalent to those of named cyclones. Consider if the long tail of a cyclone sweeps across a region, even if the eye of the storm may move off north of the island, for instance. Quite simply, the convention of naming a storm can be the difference between communities receiving support or not.

Third, the names scientists attach to forecasts matter. The policy framework for disasters in Madagascar assigns clear roles and responsibilities to organisations, and enshrines these in law. For a national committee to begin preparations for a cyclone, a warning must first be issued by the Meteorological Department. If another climate and weather centre were to issue a warning, this could not be legally considered until Météo Madagascar were to under-write this. With that in mind, our ACACIA colleagues based in the UK discussed what label they could attach to the forecasts they generated and distributed to Malagasy Red Cross, Météo Madagascar and other governance organisations. If they were to label it an ‘early warning’, for example, this would undermine the mandate of Météo Madagascar and confuse the governance system. While another label – a ‘sub-seasonal advisory’ for example – could qualify as a different yet complimentary piece of information that would fit within the system.

Taken together, the ambiguities of weather-naming conventions will need to be brought into the centre of ACACIA’s work if it is to be integrated into everyday decision-making. This will mean navigating between the names given by meteorological conventions, those enshrined in national law, and the terminology of people living in local communities.

Leave a comment